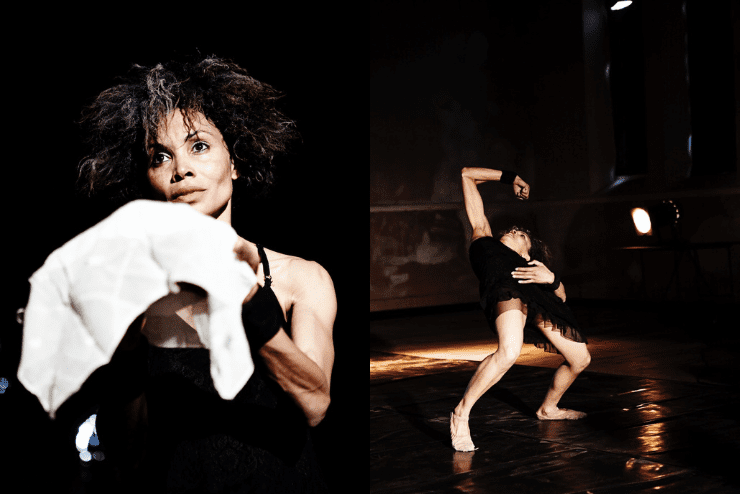

Choreographer Jackï Job is once again pushing the boundaries of dance with Ai, a brave and symbolic new Butoh ballet dance performance that heightens the senses while telling a beautiful tale. Ai translates to ‘love’ in Japanese, while Butoh ballet is a form of Japanese dance theatre centered around love, and finding it in unusual spaces.

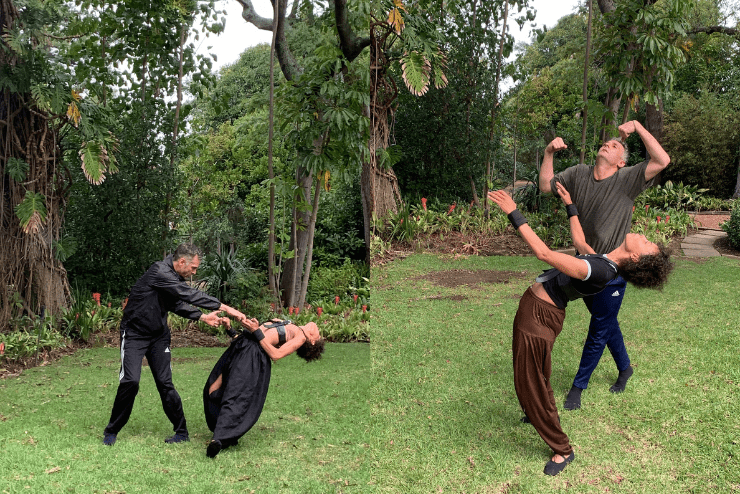

The production takes place in the quiet garden setting at Irma Stern Museum in Mowbray which is surrounded by greenery and audiences can delight in a dance between animal and human natures.

For the show, Job performs alongside Beauty, a live horse, and acclaimed French ballet dancer Alexandre Bourdat, who has recently finished a performance season at the Royal Danish Theatre in Copenhagen. She also joins forces with her long-time collaborator, award-winning classical pianist José Dias for the musical accompaniment to the showcase.

Benn Ndzoyiya had a brief chat with Jackï about her background, the ongoing creative process with Beauty, and how to drive choreography forward.

Benn Ndzoyiya: How did you start your career in choreography?

Jackï Job: I guess it was in 1994 when Mandela was president, and at the same time I went to London and I needed to create a piece that would speak about who I was. At the time, the whole world’s focus was on South Africa divided into Black and White and I thought, how do I speak about who I am and where I come from? How does one speak about being Coloured when nobody’s interested? And so I made a piece which is basically my leitmotif called ‘Daai za Lady’, a dance persona that I created of a woman that was half woman, half horse. So basically trying to find a dance language or a way to talk about my identity that cannot be described in singular terms. And that’s how it started and other works came out of that.

I’ve always wanted to have a very particular agenda with my own solo work. But as I am a choreographer, I’m also able to work with other people. And this new production Ai, a Butoh-Ballet, is very much along those lines. We started out initially with this half-woman, half-horse character, and now it’s coming to realisation 27/28 years later.

The idea in my solo performances has always been about animal and human configuration, this kind of hybrid identity. And also, in terms of the dance language. I choose something that cannot be defined in singular terms. My mission, I guess.

Was it very easy to get your foot in the door initially?

I never cared about getting my foot in the door. I think I’ve always been on the periphery, and the periphery has become a real place. A real vibrant place for me. I can sometimes move if one wants to call it, to the centre because you’re at a festival which is generally mainstream. Or I’ll be working with the opera company on the musicals. I’ll be doing things that are in the centre. But in terms of my own solo performances, I don’t think it lives in that place.

If I go back to 1994. At the time when I was in London, there was going to be the first South African cultural festival. And as I was there and doing a lot of work, I was commissioned to do a performance. Soon after they commissioned me, I get this phone call, and they retracted the commission. And I was completely confused. How is it possible I am South African doing the work? They said, no, they didn’t want me to perform. I spoke to one of the producers who was an English woman, and I said, ’you’ve got to explain to me what it is, how I cannot be included in the lineup?’ And she said, well, ‘the way you represent South Africa is not the way the British wish to see South Africa represented’. That is what the centre is about. They represent people, and they represent works to perpetuate ideas that have always been there. And so if you disturb that… unless you disturb it in the way that they prescribe.

You see I’m not doing African dance. I’m not doing ballet. I’ve resisted that kind of formulaic description. To give you an example, when one thinks of Africa in dance, there’s a drum. There have to be fiery scenes and colours. It’s got to show a lot of rhythms. Spirits of Africa. But if I look at Africa, I see that, but I also see the Karoo, and I see monotony, and I see dryness, and I see emptiness, and I see things that you can’t understand. I see one person walking in the middle of nowhere, seemingly on a mission. You don’t know where they’ve come from. You don’t know where they’re walking towards. That is also Africa. But that’s not what sells. And it’s the part that I’m more interested in.

Of course I existed all these years. It’s not like I’m saying that it’s terrible, because there is another kind of in existence as well. I’ve always made my work, and I’ve engaged with many different artists and moved inside and outside different kinds of spheres. But my own performance work, I think it sits on the periphery.

How easy was it to map out the creative process for Ai, a Butoh Ballet? I mean, this time around, you’ve got the musical accompaniment, and then also you have a live animal.

I would never have thought that I would be performing with the horse. It kind of just arrived at me. Beauty, the horse, belongs to my hairdresser Zaghra Zourtenberg who is also a very good friend. Years ago I thought it would be interesting to explore this relationship that I have with a horse and the idea of this woman/horse person. It’s not completely linear.

Alexandre Bourdat and I have been trying to do work together and he is very interested in the way I conceive my work. We started talking of ideas about how to do something together but the opportunities just never arrived.

José Dias and I have also been working together for a long time. We used to work on another production with Cape Town Opera, and then we did a series of works titled ‘And Then…’ where it’s just him and I. He’s on piano and I’m performing. It’s a series of works every year we do a new iteration.

The horse was a whole other thing. Last year in October I had a conversation with Zaghra about love, relationships, breakups, and makeups, and it just arrived. Somehow Beauty came up and she said come up and meet her (Beauty). And it was phenomenal.

Did it take very long to get comfortable with Beauty? As you know animals also work on natural impulses.

Beauty is Zaghra’s horse. They have such a tight relationship. At our very first meeting, because Zaghra was there it was fine for me to be there. But at the same time, I was also overwhelmed and I think Beauty could feel it and she was so giving. I broke down the first time. I just felt tears flowing, it was such a powerful connection with the horse. I was playing music and she let me go underneath her and over her, it was quite amazing. And then Zaghra said well now you need to figure it out for yourself. And I just visited Beauty and established our relationship.

So I dance with Beauty, we’ve got a very particular relationship. She knows when I’m there. She’s generally a very kind and gentle horse. And one feels there’s a way to communicate. You can’t hold onto any pretenses about yourself. If you do, the horse senses that and becomes almost a predator. They sense any kind of anxiety or nervous energy and pick up on everything, any sound. You’ve got to be aware that it’s a live animal and that there are other things going on that she might be alerted to. I have to be completely conscious of Beauty, but at the same time let go of consciousness. There’s this wonderful balance which I think is an incredible lesson for us as people also. How do we let go of who we are in order to see the other person? And at the same time, be aware of what the other person might be seeing, might be feeling. It’s a very delicate place and the horse is certainly teaching me that.

Why should What’s on in Cape Town audience see this production?

I think it brings together very beautiful elements. Alexandre is a gorgeous dancer who moved largely in the contemporary dance world with two decades of experience as a professional dancer. People will be satisfied with that sort of extended body that is not a 20-year-old, which is also interesting. And I think we don’t have enough of that in this country – mature dancers who are still in their bodies and moving and doing stuff. So you’ve got the satisfaction of Alexandre. The satisfaction of José who is playing a range of beautiful classical music moving from Bach, and Debussy, just beautiful classical compositions.

I incorporate very strongly Butoh, which is a Japanese contemporary dance form that I’ve integrated into my practice over the years which are the very principles that ‘Daai za Lady’ was about. Not singular descriptions of self. Not wanting to follow Western techniques. Not wanting to be in the centre. Understanding that the side instead is some place, another place. Working with ideas of uncertainty, the darkness, and the unknown. So you’ve got these very different qualities, synergising. The work is unique in its composition of elements yet it’s a very basic story about love and the difficulty in how we love and trying to find different ways of loving. That’s why it’s a classic story.

And then the show takes place in the garden of Irma Stern, surrounded by greens. The smells are gorgeous. It’s a performance where people’s senses will be alive. Visually, the ears are heightened, the smells are heightened, and the senses will be alive and heightened.

How do you rate choreography in South Africa right now, and how do our creatives differ from their peers abroad?

I’m not sure we differ. I think we try too hard to be like the ones abroad. I don’t think we’re very different because we do the same thing.

Young people don’t think of choreography as something they can aspire to. They just want to be the dancer because we have ‘So You Think You Can Dance?’ on tv and everybody wants to be the superstar. But the problem is that our training is not very good. Because when it comes to training dancers at schools, we talk about how dance can help you do maths, or help you with your problems. As opposed to looking at what it is that the actual body must do in order to hold onto dance, what must the muscles do? Instead of looking at dance as a discipline itself, we find socio-political reasons to make it valid. Whereas the form in itself is valid and we don’t see that. Because of our desperate situation in this country, and the disparities that we have, and so we find our validity is to get people off the street. Yes, that is valid too.

The scope for the imagination that can happen through the body with dance, which is where the choreographer will take them, is underdeveloped. That’s a muscle that hasn’t been worked enough. The way dancers are trained is simply not rigorous enough. There can be more rigour.

What’s next for you?

In November 2023, José and I will be doing another version ‘And Then…’ at Artscape. And in between, there are conferences and teaching. Lots of work.

What are some of your favourite spots in Cape Town?

I’m loving all the rooftop spaces. Cloud 9 Boutique Hotel has a very nice one and it’s quite underplayed. There’s always a place to sit.