Discussing the writer and illustrator’s creation of an art book series for children, and acknowledging African legends as the stories which “created the fabric of who we are”.

Written by Simona Stone.

It is somewhat rare to find an art space or initiative that is specifically aimed toward the eyes and minds of children. While children’s art education isn’t a new part the art world, we often find ourselves within art spaces that take adults seriously, and maybe children a little less seriously. Recently, I had the pleasure of chatting to author and illustrator Meridian Berndt, who is playing an active role in shifting how children can see themselves within African art spaces. She recently wrote the Zeitz MOCAA Centre for Art Education’s first children’s book series, ‘The Stories that Ran Away’.

Berndt’s involvement in this project clearly speaks to one of her callings: to use the power of storytelling to encourage young people to activate their inner potential and creative voices. Through our conversation, Berndt’s message became clear: real change can happen without having to neglect the magical and beautiful elements in our world. In fact, shining a light on them can help to enhance it.

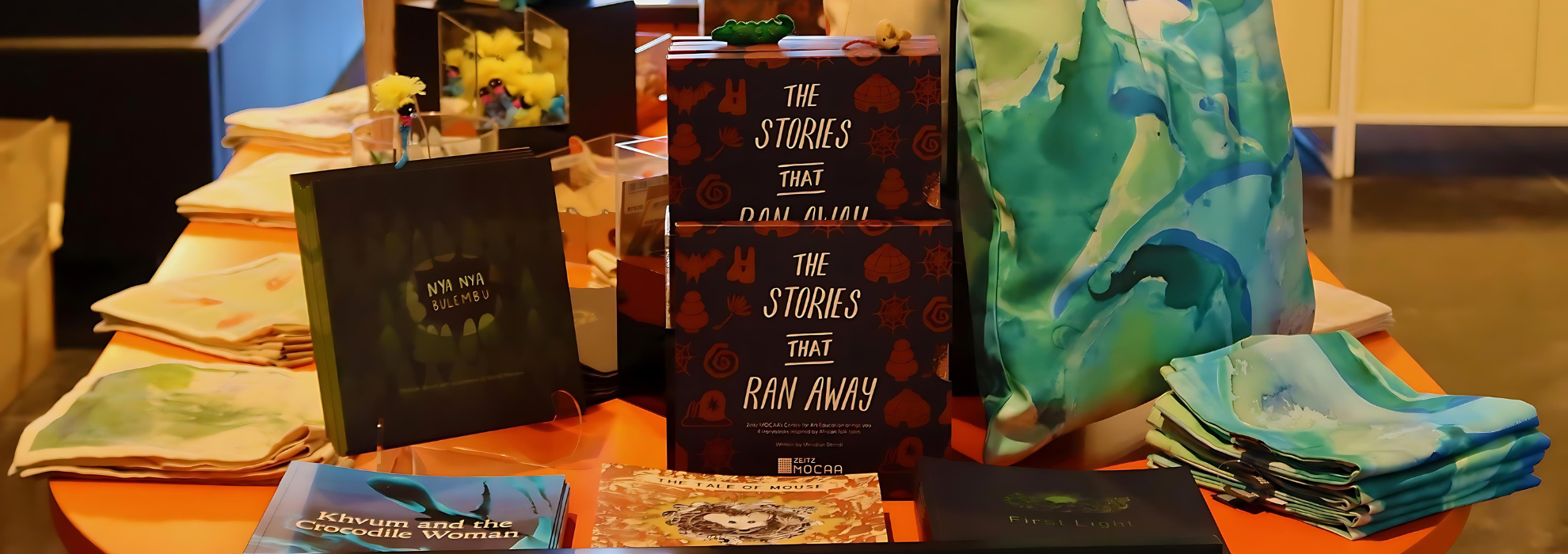

Meridian has been involved in a major collaborative project with Zeitz MOCAA, where she has written a collection of illustrated story books as new tellings of old African legends. The project emerged from an exhibition for children – held at the Zeitz MOCAA – back in 2019. The show, originally called ‘And So the Stories Ran Away’, involved students creating works to be part of the display. This recognition of children’s value in art spaces is somewhat a blueprint for the messages Berndt’s books highlight. For the past 3 years, she has worked alongside a team of illustrators and education officials at the museum to create a series of stories originating from different parts of the continent: ‘The Tale of Mouse and the Stories that Ran Away’, ‘First Light’, ‘Nya Nya Bulembu’, and ‘Khvum and the Crocodile Woman’. These stories place a lot of emphasis on the power every child possesses to make change, create beauty, and value themselves through life’s many adventures and challenges. Each book was illustrated by a different artist from a team consisting of Berndt, Jax Lamb, Jill Joubert and Mandy Wamono.

After a successful launch last month, the stories are now being shared and “brought into the light” through the museum’s Winter Storytelling Programme which has allowed children aged 5 to 12 to come and experience stories each Saturday during this month with the help of performers, puppeteers, and artists. Like much of the author’s writing, the focus is on making children feel at home within themselves and the spaces around them. These events echo the same sentiments: children can attend in their comfy gowns and slippers while enjoying hot chocolate and marshmallows.

What follows are excerpts from my chat with Meridian, and a bit more about her journey through her intertwined world of art as a storyteller and nature lover.

Could you give a brief overview of what these stories are about, and how this book series came to be?

“They came to be written because of their connection to the previous exhibition in 2019… The education arm of the Zeitz [MOCAA] really wanted to create an exhibition for children. You know, you get music for children and literature for children, but you very seldom actually get art particularly directed towards children. Being an educational institution, they invited students to come and be mentored, and create 3-dimensional, interactive works that the children would then be able to explore.

As an overarching theme of the exhibition, they decided to look at stories from Africa. That’s also another big thing that the museum is wanting to foster: more of an African presence in the world of stories, and to share those with the world. Africa is quite underrepresented in that sense. Even in our educational models here, often the stories that are used come from elsewhere. So this is just for African people – for us – to feel that our stories are valid and worth telling and sharing. And to have more of a connection to the stories that have created the stories of who we are over history, and bringing them into the more contemporary space…”

Meridian went on to explain the initial story that became the central direction for the books which followed: ‘The Tale of Mouse and the Stories that Ran Away’. In a sense, this Ekoi legend hailing from West Africa is an origin story for all stories…

“In a nutshell, it’s a story about a mouse who travels around the world and gathers all these interesting little bits of information and sensation and emotion. You can imagine this little mouse: the way she takes pieces of the known world and stores them in her burrows. Out of all these bits and pieces and diverse shards of life, she creates these ‘story children’ that live with her in her burrow. As we know about stories, as soon as they’re brought into the world, they take on a life of their own. They start to grow, transform and expand, and as they do so, they become too big to live underground, and eventually they break out into the sunlight and scatter all around the world. And that’s the origin of stories… They stayed out in the sunlight to propagate themselves and populate the world.”

So often these types of stories offer a set of morals and a way of seeing the world. It’s amazing how this process of yours reflects, like you said, the stories eventually bursting out from Mouse’s tunnel and entering into the world. It really was that kind of process at the heart of this.

“It really was, and I really feel like the stories themselves have that quality of being alive, like in this legend. I feel like they [the stories] kind of came to me. They appeared in my life and said ‘hello, we need to be written, we need to be brought into the sunlight!’.”

I was really captured by the idea of the transformative nature of storytelling. I’d love to hear a bit more about what feels important to you in terms of that power storytelling can have. What does that transformative nature look like to you?

“I think it’s been the fabric of my life in a way. Storytelling is very powerful in its ability to create change, and to shift how a person thinks or feels. Or even the way the story of the world unfolds: it can be something so small that can affect someone.

Growing up, that’s where I found a lot of my learning and my inspiration – from the stories my parents told me or the books I read. For me, to live a full life, I would like to bring something into the world that creates a positive change in some way, or something beautiful, which I feel are quite linked: the beauty and the positive transformation, even if it’s just for one person. That for me feels like a calling… That’s my offering in that way.

I feel like, with these stories in particular, they could potentially be inspiring for children and adults as well. In terms of their themes of what is possible for a human life and for life on earth. So I feel like hopefully they will be a catalyst in some way. And also even just for bringing the stories of Africa into the light, and for bringing a different narrative into the light around Africa…”

So you’ve illustrated one of the books in this series, and written all the retellings of each legend… Translating the textual to the visual: what did that process actually look like for you?

“First and foremost, as soon as you bring a visual element, you change something completely. The writing becomes something a lot more than what it was. In terms of letting go of that, working with somebody else was really interesting, because often what they brought would be quite different to what I had in my head. Luckily, the dynamic was amazing, and it just added another layer which was really exciting.

We had a lovely working spirit as a collective. We made sure to meet regularly and to share what we were doing in a safe space, but also a very honest and open, critical space… What was amazing about this project was we did work a lot together, shared meals around a table together, lots of chats and encouragement. The way we approached it was different for each illustrator, which was really amazing to see…

In my book [referring to ‘Khvum and the Crocodile Woman’, illustrated and written by Berndt], there really were only two characters and what they create together. But I feel like the environment itself is almost like a third character, because it’s so central to the story. So I thought to start with that, and see it as a living being, and start by creating that world. I kind of went wild with it, threw paint around, and used a bunch of different materials. My house was full of these massive sheets of paper that were green and blue. From there, I looked at them and drew out what I could see in terms of where the forest might be, and what the water might look like. It was more of an organic surprise rather than strictly planned…”

So, do you have a background in art making? What is the place of art in your life? And how did it come to be a part of these stories as well?

“I grew up in a very creative family. My mom was an art teacher, and my dad was a graphic designer, illustrator, and art educator who was very involved in the anti-apartheid struggle. He used artmaking and poster making – things like that – as a change-making tool. So I grew up in a house where everything was about creativity… it’s what we did for work, what we did for fun. If my brother and I got presents, they were generally a big packet of khokis. If my dad was entertaining us, he would take out this huge piece of paper and start drawing and create these worlds for us, populated by various creatures. He’d always tell us a story before we went to bed at night… so that’s how we grew up…”

It sounds like art and storytelling were both these ways of world-making for you, and creating ways of moving through the world with a lot of imagination and a lot of – as stories often give – empowerment… a lot of space to express yourself…

“Yes, I was very blessed and very privileged in that way. I feel like that’s also something I’d like to share through this: sharing that with other children who might not have that natural access to it but might find something like that through this. To access that part of themselves and the potential that lies within the magic and their inner creativity…”

I’m interested to hear a bit more about any experiences or interactions with the natural world which might have had a role in this journey for yourself…

“I think it’s always been so intrinsic to who I am. In a way, I don’t really understand how we can care about anything else more… it’s the most important thing. It needs us, we need us. Because it isn’t us versus ‘it’. We are that. I feel like sometimes there is such a disconnect from that: like there is the natural world and then there are humans. Having lived out of the city and having my feet more in the earth had me more in tune with knowing. Living in the city environment, it’s easier to forget. But its amazing, there are reminders everywhere. It’s just about looking and feeling. Even if it’s just a bedraggled starling on your washing line, that can remind you. I feel like that’s so fundamental now more than ever, to remember that. There is a humility in that.”

Especially, you’re writing for kids who are the next generation, and they are inheriting a very scary natural world, and a precarious environmental situation…

“In many ways, their elders have failed them. They’re going to have to come to terms with that and see how to move forward. Hopefully, I’d like to see within my lifetime a positive shift within that space. Even if I can be a tiny, minute, little part of that, that would be amazing. I’ll feel like it was a life worth living…”

Do you feel like – in the same way with storytelling – that your art-making is also really inspired by the environment?

“Oh yeah, it’s all intertwined, definitely. I suppose it’s also quite therapeutic as well: we do have to continue because the world isn’t perfect. Stories and art-making and all those creative things can really be very therapeutic for people of all ages to engage with. Not just with having to learn something, and making the world better, but just in a way of feeling better. With the beauty that’s still here: it’s not that the world is completely trashed. There is still so much beauty, and to focus on it is also powerful. When you focus your attention, that also expands, and that is also very important… it’s a tool to remember and notice the good and the beautiful and the true that is still here. It’s not only all ‘doom and gloom’, but to shine a bit of a light on what is beautiful and positive and alive and adaptable and evolutionary and revolutionary and possible.”

I’ve picked up by researching on these books that they are talking so much about an imaginative tapestry woven together. Almost – like in your creative processes and embodied within this book – there is this process of binding and combining a variety of different interests and practices and beautiful things and characters which are alive. Would you say that these books are one of those finished products of having these different ideas woven together, that almost become like the fabric for change?

“Definitely. And enjoyment. I feel like enjoyment is also really important. We want the fabric for change, but we also want to enjoy it, and it also needs to be beautiful. The joy of life can also be overlooked when you’re trying to change the world. In activism, I feel like beauty, joy and pleasure are also really important. That’s also a revolutionary act, in a way: to take pleasure. I really wanted the books to be beautiful, and I feel like they are, and I’m happy about that… The energy of the group is so special, and that’s really imbued the project with a joyfulness and a good feeling, which I definitely couldn’t have created in isolation. It’s definitely a team that brought this into the light…”

Is there something that drew you to writing for children as opposed to writing for adults?

“Because there’s a lot of space for things to be magical and poetic. It flows easily for me to write that way, because it comes from a place inside of me. It’s not so cerebral, and I’m moved by it, rather than having to think it through. It feels like it’s working through me… Children have a much more diverse palate: they’ve got this spongey nature where they’re open to absorb all sorts of things… this openness to receive the magical and the beautiful and the mysterious. Which, incidentally, I hope that this can also unlock for adults as well. If they engage with this material, that same childish wonder will be evoked for them… I hope it can be beautiful for all sorts of people…”

The Stories That Ran Away will continue to be read for children through the Zeitz MOCAA’s Winter Storytelling Programme, which runs until Saturday 24 August 2024. This Saturday, Khvum and the Crocodile Woman will be the chosen story for reading. Books are available for purchase at the museum shop before the start of reading sessions.

Cost: Winter Storytelling Program sessions are free for children but booking is essential. Book here | Adults pay museum entry fee of R250 or free with museum membership | Books are R150 each | Full book set available for R600

When: Last reading session will be Saturday 24 August, 4pm to 6pm

Where: Zeitz MOCAA, Silo District, South Arm Road, V&A Waterfront, Cape Town